A novel treatment option for canine OSA is a vaccine-primed adoptive cell therapy that targets the patient’s specific cancer.

Sponsored content by Elias Animal Health

Cancer is the leading cause of death in dogs over two years of age and remarkably, one in four dogs will develop cancer in their lifetime. Pet owners and their families are urgently looking for new and better treatment options that not only extend their companion’s life but also improve the quality of life. This article discusses a novel immunotherapy for dogs with osteosarcoma (OSA).

Osteosarcoma (OSA) is the most common primary bone tumor seen in dogs. Other bone tumors (chondrosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, hemangiosarcoma, metastatic tumors) are possible but much less frequent. OSA most commonly occurs in middle-aged dogs, although there is a small population of dogs that will develop it at a young age of one to two years old. The cause of this cancer is unknown, but clearly there appears to be a genetic component. The most commonly affected breeds include Saint Bernard, Great Dane, golden retriever, Labrador retriever, Scottish deerhound and Rottweiler.

Other proposed causes include microscopic injury to bones in young growing dogs, metallic implants and trauma. OSA occurs most commonly within the distal radius, followed by the proximal humerus, distal femur and proximal tibia; however, this cancer can develop in any bone. In dogs, OSA is characterized by destructive primary tumor growth, the presence of microscopic spread in up to 90% of cases at the time of diagnosis and an aggressive course of disease progression with metastasis to the lungs in less than one year in untreated dogs.

Treatment.

Definitive local therapy.

The current standard of care treatment approach for OSA consists of local control (surgery) and systemic control (chemotherapy). Since most OSAs are located in the appendicular skeleton (aka the “long bones” of the limbs), full limb amputation is typically recommended. In certain cases, limb-sparing surgery may be possible, where only the affected portion of the bone is removed and is reconstructed with another bone (allograft) or metal spacer (endoprosthesis). This type of surgery is generally reserved for patients with OSA affecting the distal radius and is associated with a high rate of postoperative complications (implant failure, infection and tumor regrowth).

Stereotactic radiotherapy (aka SRT, stereotactic radiosurgery/SRS, CyberKnife).

A non-surgical limb-sparing option is also available using radiation therapy, called stereotactic radiosurgery, and this can be used for OSA in any location. Stereotactic radiotherapy involves the precise application of >1000 beams of radiation aimed from various different angles in order to deliver a high dose of radiation to a designated tumor target, all while sparing the surrounding tissues (such as the skin). In some cases, such as CyberKnife, this treatment may be given by a robotic delivery system. Complications of stereotactic radiation therapy include fracture from radiation-induced bone necrosis and tumor regrowth. The early data was quite promising documenting survival times similar or better to that with amputation and chemotherapy, however, more recent studies suggest this may not be the case, with survival outcomes similar to those achieved with standard palliative radiation therapy.

Systemic therapy.

The best outcomes for dogs with OSA to date have been for those undergoing amputation followed by chemotherapy. Numerous chemotherapy protocols have been evaluated. Two studies suggested the best outcomes are achieved with a protocol consisting of six doses of carboplatin, given as intravenous injections every three weeks. Other commonly used protocols include a four-dose course of carboplatin, alternating carboplatin and doxorubicin (three doses of each) or doxorubicin alone (five doses every two to three weeks). Side effects with such chemotherapy protocols are typically predictable, manageable with supportive therapies and occur with rather low frequency. The financial commitment for chemotherapy for a large breed dog is not inexpensive and often approaches $4000-6000, depending upon geography.

Palliative care.

For dogs whose owners elect not to pursue definitive therapy, general palliative care measures may include analgesics such as tramadol, gabapentin and amantadine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as carprofen, deracoxib or piroxicam, and alternative approaches such as acupuncture. Radiation therapy can also be used in a palliative setting, typically given in lower overall doses than that used for stereotactic radiotherapy. Protocols available include the administration of two sequential treatments on back-to-back days or once weekly treatments for three to four sessions. The huge majority of dogs will derive some analgesic benefit from radiation within the first one to two weeks, but typically only for a period of a few months. Oftentimes patients undergoing radiation therapy are also given bisphosphonates, which are “bone filler” medications administered as IV infusions and aimed at reducing bone destruction and pain.

Prognosis.

The median survival time for dogs undergoing surgical tumor removal followed by conventional chemotherapy for OSA is approximately 10 to 12 months, with a one-year survival rate approaching 50%. The two-year survival rate for dogs undergoing surgery and chemotherapy ranges from 15-20%, depending upon the study referenced. Dogs that undergo radiation therapy +/- bisphosphonates/chemotherapy typically have survivals in the four-to-eight-month range, while dogs that do not undergo cancer-specific therapy typically are humanely euthanized due to uncontrolled pain within one to two months of diagnosis.

Negative prognostic factors include higher body weight (giant breed dogs), elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP – a measure of bone destruction on serum chemistry screen), elevated white blood cell counts and proximal humerus location. Dogs with tumors arising on the mandible, ulna and metacarpals/metatarsals/digits tend to have a slightly lower metastatic risk and longer survivals with aggressive therapy. With the increasing amount of research being devoted to adjuvant immunotherapies, the goal of veterinary oncologists has become to increase the proportion of long-term survivors, all the while ensuring that each patient maintains an excellent quality of life both during and after therapy. Surely, we have more to learn and there is plenty of room to improve patient outcomes.

Novel immunotherapy: ELIAS cancer immunotherapy (ECI®) (ELIAS Animal Health).

There is now a novel treatment option for canine OSA called ELIAS cancer immunotherapy (ECI®). ECI is a patented vaccine-primed adoptive cell therapy that targets the patient’s specific cancer. Autologous cancer cell vaccines are used to condition the immune system (T cells) to recognize the cancer neoantigens. Vaccine-primed T cells are harvested at apheresis for ex vivo expansion and activation. Activated killer T cells are administered by IV infusion.

Data from a single-site, single-arm, open-label prospective trial of vaccine enhanced ACT using low-dose IL-2 in client-owned dogs with OSA at the University of Missouri Veterinary Health Center (MU-VHC) was recently published. The study was designed to determine the safety and efficacy of this immunotherapy as a treatment for dogs with OSA. It was hypothesized that dogs with OSA could be treated safely by ex vivo-activated T cells that were generated by autologous cancer vaccination and supported by low-dose IL-2 treatment, and that dogs would survive more than twice as long as reported for amputation alone. The primary endpoint of the study was survival fraction beyond 268 days (twice that of amputation alone) in a single-stage phase II assessment according to a previously described method.

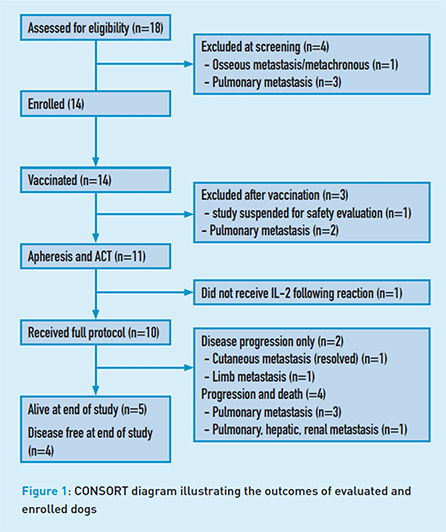

Eighteen dogs were assessed for eligibility with four excluded at screening (pulmonary metastasis n=3, bone metastasis n=1) leaving 14 dogs to enroll. All dogs underwent amputation and excised tumor tissue was used to create the autologous vaccine which was subsequently administered intradermally to all 14 dogs. Three dogs were excluded from the study post vaccination (safety evaluation n=1, pulmonary metastasis n=2). Eleven dogs underwent leukapheresis and mononuclear cell products were stimulated ex vivo with a T-cell-activating agent. Activated product was transfused and five subcutaneous IL-2 injections were administered q48h. Dogs were monitored for metastasis by thoracic radiography every three months.

Toxicity was minimal after premedication was instituted before activated cell therapy. With premedication, all toxicities were grade I/II, however, it is important to note that serious infusion reactions requiring medical management can occur (e.g., cytokine release syndrome). The median disease-free interval for all dogs was 213 days. Median survival time for all dogs was 415 days with five dogs surviving >730 days (range 523-731). Interestingly, one dog developed cutaneous metastasis but then experienced spontaneous complete remission.

Why is this important?

The median survival time of 415 days for dogs treated with amputation and immunotherapy in this study was longer than previously reported survival times using amputation and four-dose carboplatin. Here’s what the company says: “We (ELIAS) brought the technology over from a human health company with the hopes that we would be able to significantly improve the survival times and quality of life for dogs being treated for cancer. What’s really cool about the work we are doing is the relationship between human cancers and canine cancers. We believe our work will change the way canine and human cancers are treated in the future.” – CEO Tammie Wahaus.

The study showed that 50% of dogs treated with ECI survived beyond one year and 36% survived beyond two years. Key experts in the field of veterinary oncology are impressed by the results from early study on this novel therapy: “I really think that there is strong evidence that the ELIAS procedure benefited these dogs substantially and on average, based on that median survival. I will also point out that every single piece of the ELIAS immunotherapy process is extremely well supported in the scientific literature across multiple species.” – Dr. Jeffrey Bryana.

“The T cell expansion is a huge component that to my knowledge, none of the other autologous products are even trying to replicate.” – Dr. Zachary Wright*.

Although the early data is quite promising, one must keep in mind the small number of cases in the original study. Having said this, a large prospective randomized trial comparing the outcomes of dogs receiving adjuvant carboplatin vs. ECI has recently completed enrollment. If similar results are demonstrated, it is these authors’ opinion that ECI could become the new standard of care for canine OSA.

Licensure status: Autologous prescription Product, Code 95A7.50 (unlicensed by USDA) and is pending full licensure. ECI is distributed as an experimental product under 9 CFR 103.3. For use under supervision/prescription of a licensed veterinarian. A randomized pivotal trial (Carboplatin vs ECI) has recently completed accrual and data is maturing.

*Quotes are from a KOL roundtable sponsored by ELIAS

Note: This article ran in DVM360 in October 2021.