Localizing respiratory distress can be tricky. Look for these signs to help properly diagnose and treat the patient.

Nearly every day, dogs and cats enter our hospitals with concerns about respiratory distress. While some are clearly not in active distress (think reverse sneezers or kennel cough dogs), some certainly are and require gentle care to prevent worsening of their symptoms. In patients that are so distressed that obtaining full initial vitals might be detrimental, there is crucial information that can be obtained non-invasively to help determine the underlying issue and next steps.

1. Which phase of breathing is taking longer?

a. Inspiration takes longer.

This is classic for issues from the larynx forward (i.e., upper respiratory distress). Think congested noses, oropharyngeal swelling, brachycephalics in distress, laryngeal paralysis, severe collapsing trachea, etc. A sedated airway exam is likely a good next step, and if you’re taking chest radiographs, I’d be sure to include at least one lateral view of the cervical region.

b. Expiration takes longer.

Patients who struggle or have more effort on expiration classically have lower airway disease as their primary issue. If you have access to a bedside ultrasound, this can help narrow your list of differentials quickly while the patient is still in oxygen (are there B-lines? Shred sign? Effusion?). If not, chest X-rays are the next best step.

2. Are they making audible noises?

a. Stridor.

This is the high pitched, inspiratory wheezing sound of an upper airway obstruction. Think classic laryngeal paralysis. Sedation +/- active cooling is likely the next best step in these pets, sometimes enough to perform a sedated airway exam.

b. Stertor.

This is the snorty, snuffly, thick, deep sound that signifies turbulent interference of soft tissues with the upper airway – usually on both inspiration and expiration, sometimes worse on one of those phases. Think “normal” brachycephalic breathing. Again, sedation is key to decreasing the stress of breathing and avoiding worsening distress.

c. Combination.

When oropharyngeal swelling or inflammation or collapse is severe enough to cause a near-total occlusion of the trachea, you can have both of these sounds concurrently or on different phases of breathing.

3. Is it a cat?

Cats in respiratory distress are sometimes the most challenging patients since their symptoms can rapidly escalate from mild to life-threatening, and stress can absolutely push them over the edge. You can still use the above criteria to help you out, but a tremendous amount of information can be gained from a brief thoracic ultrasound if at all possible, sometimes after a few minutes to “decompress” in oxygen with minimal handling as well as sedation. Some tips include approaching slowly, working through the little porthole in the oxygen cage door, applying a small amount of alcohol, and sneaking in the bedside ultrasound probe. The main goals with a point of care ultrasound are determining:

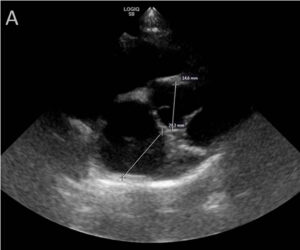

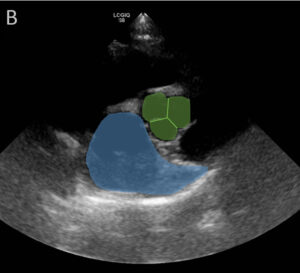

a. What is the La:Ao ratio?

This is my best way of quickly including or excluding congestive heart failure as a cause for distress. I look from the right side, just behind the elbow, and aim for the opposite thoracic inlet or shoulder region. Ideally, you catch the picture at the level of the aortic valve, where the aorta has a clover shape (or looks like a Mercedes-Benz sign) and the left atrium/appendage looks like a sideways comma (or a whale). I measure across the aorta (I usually measure the diameter in a 12 o’clock to 6 o’clock direction) and measure the left atrium (I usually go from the point where my aortic measurement stops and head in a 6-to-8 o’clock direction across the head of the comma-shaped left atrium/appendage). While there is mild variation among sources for “normal” La: Aos, I find 1.5:1 easiest to remember and calculate as the upper end of normal. A ratio of 2:1 or more bumps congestive heart failure, or at least very advanced heart disease, to the top of my list, especially if there’s pericardial or pleural effusion.

b. Are there numerous to infinite B-lines?

This helps me gauge severity. The more B-lines, the more severe the pulmonary edema (bad enough to extend to the peripheral lung field). This is enough to have discussions about the critical nature of the cat and give an approximation of time to perform workup/diagnostics.

c. Is there effusion?

Pericardial effusion in a cat is uncommon, but when it occurs it is usually associated with congestive heart failure. Accumulation of a sufficient volume of pericardial effusion to cause tamponade (think dogs with heart base masses) is even less common, so I’ve rarely attempted pericardiocentesis in a cat. On the other hand, finding and removing pleural effusion gives me both a therapeutic and diagnostic procedure to perform that can rapidly improve patient stability and lead to specific diagnosis.

d. Naturally, not everyone has an ultrasound at their beck and call.

If a fast scan is not possible, then careful auscultation is your next best bet, followed by thoracic radiographs if the patient is stable.

Struggling with medication decisions in these patients? Butorphanol is my go-to medication for a little sedation in any cause of respiratory distress (0.2mg/kg to 0.4mg/kg IM or SC). This can also be given as they head out the door for a referral center to help minimize car-ride stress and help the patient stay alive until admission. If congestive heart failure is high on my list of differentials, I also am generally comfortable giving a single dose of furosemide (1-2 mg/kg in cats or 2-4 mg/kg in dogs, IM or SC) while waiting for additional information or awaiting owner decisions. I always ensure that any patient given furosemide has access to water, as well.

If the hardest part of respiratory distress management for you is the adrenaline rush or panic that accompanies these patients in your treatment area, just remember: you must also breathe to provide optimal care. Let your techs place these pets in an area where they are minimally restrained (this wins for me over restraint for oxygen supplementation) and, if possible, without additional stress, provide supplemental oxygen. Breathe. Watch the patient. Breathe some more. Look for the above signs. Then press on!

A) Left atrium: Aorta (La:Ao) measurement examples on a normal canine heart. La measures 20.3mm and Ao measures 14.6mm, resulting in a La:Ao of 1.39.

B) Highlighted regions are the comma-shaped left atrium (blue) and the aorta (green region) at the level of the aortic valve (green lines).